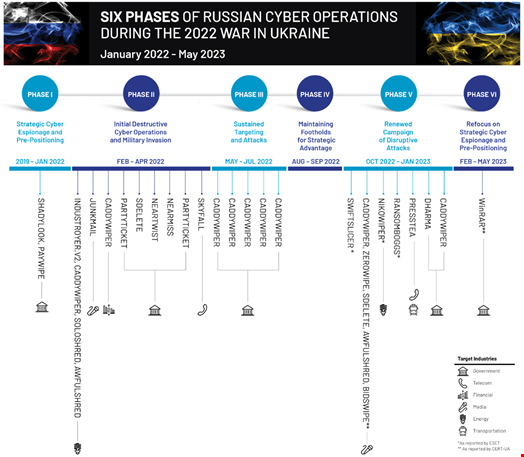

Drawing on its tracking of Russia-backed disruptive operations against Ukraine since the country’s invasion of its neighbor in February 2022, Mandiant observed that multiple distinct Russian threat clusters have been persistently using the same, repeatable playbook throughout the war to pursue Russia’s information confrontation objectives.

The cybersecurity firm, now part of Google Cloud, presented its findings in a blog post published on July 12, 2023.

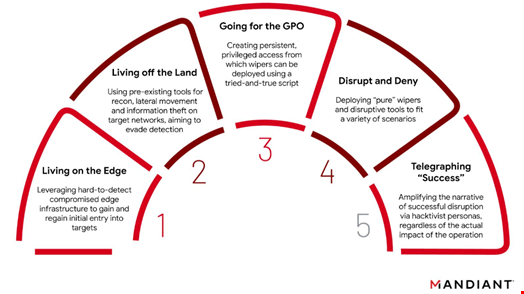

This playbook, crafted by the Russian military intelligence service (GRU), contains the following five operational phases:

- Living on the Edge: Leveraging hard-to-detect compromised edge infrastructure such as routers, VPNs, firewalls and email servers to gain and regain initial access into targets

- Living off the Land: Using built-in tools such as operating system components or pre-installed software for reconnaissance, lateral movement and information theft on target networks, likely aiming to limit their malware footprint and evade detection

- Going for the GPO: Creating persistent, privileged access from which wipers can be deployed via group policy objects (GPO) using a tried-and-true PowerShell script

- Disrupt and Deny: Deploying ‘pure’ wipers and other low-equity disruptive tools such as ransomware to fit a variety of contexts and scenarios

- Telegraphing ‘Success’: Amplifying the narrative of successful disruption via a series of hacktivist personas on Telegram, regardless of the actual impact of the operation

Typically, after an initial reconnaissance, Russian cyber operations since the beginning of the war in Ukraine would start compromising systems with the ‘living on the edge’ phase. Then, the adversary would establish a foothold in the system, maintain its presence and escalate privileges with ‘living off the land’ methods. It would then combine these methods with group policy objects to move laterally and conduct further reconnaissance within the internal systems. Finally, it would deploy the malware (wipers, ransomware…) and launch a Telegram campaign to amplify the operation’s success at the same time.

A Deliberate Effort from the GRU to Go Quick and Dirty

Mandiant has observed that this same playbook has been used by various threat actors throughout the six phases of the war identified by Mandiant researchers – five of which were outlined in Google Threat Analysis Group’s (TAG) February analysis, reported by Infosecurity.

This led Mandiant to confirm the GRU’s “central role in standardizing operations across multiple subteams in an attempt to deliver more repeatable, consistent effects,” the report reads.

As most phases aim to deploy and execute disruptive malware quickly while avoiding detection, Mandiant noted that the playbook is “notably suited for a fast-paced and highly contested operating environment, indicating that Russia’s wartime goals have likely guided the GRU’s chosen tactical courses of action.”

The company also assessed “with moderate confidence that this standard concept of operations highly likely represents a deliberate effort to increase the speed, scale and intensity at which the GRU could conduct offensive cyber operations while minimizing the odds of detection.”

A Shift from Previous GRU Methods

Dan Black and Gabby Roncone, the report’s authors, also noted that while the general intent of the GRU is aligned with previous Russia-aligned cyber campaigns – “to irreversibly destroy data and disrupt the ability of target systems to function as intended” – the design of the disruptive malware the GRU has chosen to use during the war is substantively different from what was previously observed.

Read more on Mandiant’s 2023 M-Trends report

First, since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Russian threat actors have shifted from deploying pure, sometimes pre-packaged, disruptive tools that can be used immediately – but that were usually not reused much – to multifunctional and highly reusable ones.

Second, the GRU has extended its use of “noteworthy political actors and hacktivist identities” in its disruptive playbook. From 2014 to 2018, Mandiant saw the emergence of several ‘personas’ (CyberBerkut, CyberCaliphate, Guccifer 2.0…) that allowed the GRU “to misdirect attribution and generate second-order psychological effects from their cyber operations.”

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, some new, self-proclaimed hacktivist groups have started appearing (CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn, XakNet Team, Infoccentr…). These took a more active role than the previous category of personas: besides supporting the Russian regime, they actively amplified and exaggerated the impact of the cyber-attacks conducted by Russian hackers, and some were even observed to leak data from victims who were also affected by wiper attacks. All this primarily happened on Telegram, “which has emerged as a critical source of sensemaking, war-related information operations, and a key recruitment platform for volunteer cyber “armies” in the conflict,” wrote Mandiant researchers.

UNC3810 and CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn’s Links to the GRU

One notable example highlighted by Mandiant is the deployment of CaddyWiper in October 2022 by a threat group the cybersecurity firm tracks as UNC3810.

The researchers wrote: “In the final stage of the playbook, data from the victim of UNC3810’s wiper attack was staged and advertised on Telegram by ‘CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn,’ […] that claimed responsibility for the wiper attack. However, technical artifacts from the UNC3810’s intrusion indicate that the ‘CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn’ persona severely exaggerated the success of the wiper attack. Due to a series of operator errors, UNC3810 was unable to complete the wiper attack before the Telegram post boasting of the disrupted network. Instead, the Telegram post preceded CADDYWIPER’s execution by 35 minutes, undermining CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn’s repeated claims of independence from the GRU.”

According to Dan Black on Twitter, this operation failure shows the two groups’ “integrated forward planning and the Telegram channel's high confidence links to the GRU.”

alt pitch: come for the Playbook, stay for the "oopsies" https://t.co/TfEFLV6eay

— Gabby Roncone 🌻 @gabr.bsky.social (@gabby_roncone) July 12, 2023

In its conclusion, Mandiant said it “anticipates that similar operational approaches, or ‘playbooks,’ may be mirrored in future crises and conflict scenarios where requirements to support high volumes of disruptive cyber operations are present.”